|

Do you want to learn more about DBI and our upcoming training opportunities? Now’s your chance!  Join our co-directors CM Hall and Heather Holmes for DBI’s first webinar! This webinar is an introduction and opportunity to learn about the work and progress that the DeafBlind Interpreting National Training & Resource Center has made since beginning research into effective practice in DeafBlind interpreter education. Through in-depth surveys, focus groups and interviews, DBI has identified key findings as well as core competencies and domains that any interpreter working with DeafBlind individuals should be aware of. This hour-long webinar will introduce you to the co-directors and core team members on the grant as well as introduce the emerging research into protactile ASL as linguistically distinct from Visual ASL. A pre- and post-assessment and evaluation will be required of those seeking CEUs. At the conclusion of this webinar, participants should be able to identify the domains and competencies related to DeafBlind interpreting work and determine how it is different from visual ASL interpreting. This webinar is open to all and is available for CEUs. Being awarded CEUs is contingent on completion of a pre- and post-assessment. Registration is FREE and includes access to all future public training content on the DBI Moodle site. Webinar: DBI Moving Forward: From Research to Practice Available on demand starting Monday, February 19th Not sure if you can participate right away? You should still register! We will keep the recorded content available to all registrants for 90 days.

Having trouble getting started? Need an alternate format sign-up form? Contact us at dbi@wou.edu or 503-888-7172 (voice/text/FaceTime) *Please note: In order to receive CEU’s, you will be required to complete pre- and post-tests and a minimum of 75% of content. 0.125 CEUs in the category of Professional Studies will be offered by the Regional Resource Center on Deafness at Western Oregon University, an approved RID CMP and ACET sponsor. The DeafBlind Interpreting National Training and Resource Center is conducting a national needs assessment survey to assist us in identifying current and emerging practices in the field of DeafBlind interpreting. The goal of this survey is to identify specific competencies required for interpreters who work with DeafBlind consumers. The term DeafBlind will be used throughout the survey. For our survey purposes, the definition includes individuals who are DeafBlind, deaf-blind, and/or who have a combination of hearing and vision loss, those who are late-deafened with vision loss, hard of hearing with vision loss, close vision, or are oral deafblind. This survey will take about 20 minutes to complete, depending on your answers to some of the questions. You must answer the first question so we can know you have read and agree with the Consent information. The results of this survey will assist in determining the skills and competencies expected of DeafBlind interpreters. Please share the survey link widely as we are working to reach as many professionals who work with people who are DeafBlind as possible. The survey link is here: http://woutri.az1.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_1RdibQTyoGC6t93 The survey will close on Sunday, October 15th at 11:59pm. Thank you! (Video transcript and description also available for download as an accessible Word document) Video Description:

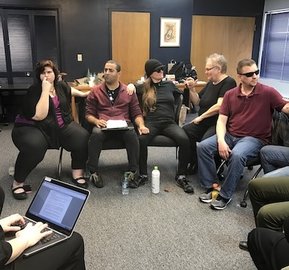

Roberto (Latino male, with short hair, black rimmed glasses, and wearing a dark button down, three-quarter length sleeve shirt) stands in front of a dark curtain and signs into the camera. Video Transcript: Hello! I'm Roberto. I am DeafBlind. I am a VR counselor and I teach American Sign Language. I work with DBI – The DeafBlind Interpreting National Training and Resource Center. We're about to send out a survey and we need your help. Are you DeafBlind, Deaf, hearing, sighted, hard of hearing, or low vision? If so, please fill this survey out. Do you work as an interpreter, an interpreter educator, or a VR counselor, or in some other field related to DeafBlind individuals? If so, please fill out this survey. It will only be available for a limited time, two weeks in fact. It will close October 13th, which is next Friday. Please be sure to fill it out before then. Thank you! I first volunteered at a weekend DeafBlind camp on the side of Mt. Hood near Sandy, Oregon in the fall of 1992. I remember having perhaps my first and only panic attack on the way up driving past snow. I was starting to freak out, thinking “I’ve only been studying sign language for a year! How am I going to guide or interpret with DeafBlind people in the snow?!” My friends calmed me down, and I made it through the weekend. All the DeafBlind people lived. I remember one moment during the weekend when I was matched with a DeafBlind senior citizen who was wearing overalls. They were announcing the winners of the costume contest and the person I was interpreting for won for Best Overall (people thought it meant, Best Overalls.” A more seasoned interpreter saw that I wasn’t getting the message across and asked if I needed help and he intervened. I was grateful because the goal of that man getting the message that he won was getting across more swiftly than I could have. After that weekend, I wasn’t sure volunteering in the DeafBlind community was right for me, but my friends and I returned the next spring to the weekend camp on the Oregon Coast. I think that was the camp that cemented my volunteerism as a passion for me. I had a lot of fun with other volunteers and met some pretty interesting and dynamic DeafBlind people too. I saw the magic that transpires when this community comes together and I was hooked. From there, I sought out an interpreting internship with more opportunity to be in the DeafBlind community in the Bay Area. I continued to volunteer at the Oregon camps through the mid 1990’s until money ran out and the camps couldn’t operate any longer. I had heard about Seabeck, the DeafBlind Retreat that had been operating for decades (now almost 40 years) in the Olympic peninsula of Washington State. The week-long retreat accommodated 80 DeafBlind folks and 150 volunteers. I first went in 1998. I was excited to see many of the same DeafBlind individuals and volunteers who had come down by bus for the Oregon DeafBlind camps. I started working for the Western Region Interpreter Education Center grant at Western Oregon University in 2007. I heard about service-learning as an opportunity for students to apply their studies through meaningful community service with instruction and reflection and thought about how Western was well-positioned to collaborate with the DeafBlind community, a community always in search of qualified, ASL-fluent interpreters and sighted guides. I began to reach out to the Seattle DeafBlind community leaders and initiate a relationship. I’d been away from active volunteering in the community for a decade and there were new faces and I wanted to work to create a project with students to train them. Soon after our relationship was underway, Seattle Central Community College’s interpreter program was disbanded and building that relationship was even more valuable especially as many Western students hail from Washington. In the 12 years since I first taught Western students about DeafBlind interpreting and guiding, 135 students have gone to volunteer at Seabeck. These students have been hearing, Deaf or hard of hearing. Many students have found their spiritual home and community at Seabeck and return year after year to volunteer now on their own, as they have built their own relationships with DeafBlind community members and other volunteers. Western has also built a strong relationship with the active volunteer organization, WSDBC, the Washington State DeafBlind Citizens. This group has quarterly meetings and works with us to provide volunteers so that their members can actively plan and engage in their community. I’m proud of the way we work to show up. Aware of our privilege and power and working to affirm each DeafBlind individual’s dignity, worth and right to access and information through touch. This partnership is a journey we are on with WSDBC, the DeafBlind Service Center, and The Lighthouse for the Blind which plans the Seabeck Retreat, and we strive to honor the DeafBlind community’s experience first in. We see how much value and learning is gained and because of this relationship, we are better able to prepare our graduates to go on and work with other DeafBlind individuals and pursue their passions with this community. I continue to be amazed at how opportunities have opened up for interpreters to work with DeafBlind individuals, traveling for conferences, cruises, workshops, and the like. Witnessing students who are no longer students in most cases using ProTactile ASL and being open to how to grow and learn more is a wonderful affirmation that the relationship we continue to build and work on is worthwhile. -CM Hall CM HALLCM Hall, Ed.M., NIC Advanced, EIPA K-12, is the DBI Project Manager. CM has volunteered in the DeafBlind community since 1992 and created an academic service-learning project for ASL-fluent students to engage with the DeafBlind community, partnering with the Washington State DeafBlind Citizens organization and the annual Seabeck DeafBlind Retreat. Thinking about holding our first big grant meeting for the DeafBlind Interpreting National Training & Resource Center over three days in Seattle with a majority of the meeting participants being DeafBlind community leaders and key stakeholders was exciting. Simultaneously, I imagined potential challenges could arise, but having been a part of this community for over two decades, I knew it would also present intangible –and literally tangible—rewards that regularly remind me why I got into studying interpreting and Deaf/DeafBlind Culture. Sure, it was a lot of advance work to coordinate all the travel, lodging, meeting location details, SSP and interpreter logistics. Yet once everyone comes together and there is ProTactile ASL as far as you can touch, it makes all those pesky details melt. It’s what we aspire to create in this grant: a PTASL-accessible environment for everyone. It was an education for all involved—learning about our grant goals and activities over the five years, and learning how to give in-the-moment information and feedback that affirms our inclusive environment and an autonomous one for all. It was a long three-days, but the immersive environment was a great refresher for those more experienced in PTASL and opened up a whole new world and created a lot of “aha!” moments for those who were touching it for the first time. I can’t wait to see how many more folks, DeafBlind, hearing/sighted, hard of hearing, are all more PTASL-savvy at the end of this grant. I hope we feel a little closer to one another and validate the DeafBlind community’s language in the process. Touch you later, ~CM CM HALLCM Hall, Ed.M., NIC Advanced, EIPA K-12, is the DBI Project Manager. CM has volunteered in the DeafBlind community since 1992 and created an academic service-learning project for ASL-fluent students to engage with the DeafBlind community, partnering with the Washington State DeafBlind Citizens organization and the annual Seabeck DeafBlind Retreat.  A few weeks ago we had our first meeting with our Core Team in Seattle, Washington, and it was my first foray into DeafBlind culture. The meeting included 4 DBI staff (all hearing/sighted), 4 individuals who are DeafBlind, and one hearing/sighted VR counselor with a DeafBlind caseload (an RCDB). Of the four DeafBlind individuals, two were the developers of ProTactile (and contractors on the project), one was a VR Counselor, and one teaches in an interpreter training program educating students about working with individuals who are DeafBlind. There were also six interpreters working with three of the DeafBlind individuals (three hearing and three deaf). The meeting was conducted in ASL. Hearing/sighted norms had no place here. First, spending the time to get to know who was there and to get to know each other was important. In this situation, we all lined up in two rows facing each other. We each chatted a few minutes with the person across from us, and then switched partners. It was a very intentional way of leveling the playing field. It wasn’t just the hearing/sighted people who knew who was there and who could get a feel for the different personalities in the room. Once we had all talked with each other, we were ready to join the circle; no rows of chairs and tables for this group. For one thing, people aren’t likely to be taking a lot of notes on computers if they are relying on some type of tactile sign language. And there are often lighting challenges for people with low vision. Going from room lighting to looking at the computer lighting may be very tiring for their eyes, which are already taxed in a 3.5 day meeting. Thus, having a designated notetaker (a talented team member who could watch the language and take notes at the same time) was important for everyone, but not so with tables. Tables also get in the way. DeafBlind culture is a culture of touch. When you are sitting next to someone, you always stay in physical contact, whether through your leg or foot up against theirs, or having your hand on their thigh. This is so they know you are still there, and it allows them to know if you are agreeing or disagreeing with a speaker (for example, by patting their leg) without interrupting the interpretation. (If you are talking, they will also have a hand on your thigh indicating they are following you). The interpreters all needed to be able to see who was signing so that they could interpret in PTASL, and tables definitely get in the way of the flexibility that is needed. As someone who currently knows very little about the features of PTASL, it was fascinating to me to watch and try and figure out what was being done differently and why. For example, I noticed that when a speaker is setting up a sequence (e.g., 1st, 2nd, 3rd), she indicated the sequence on the other person’s fingers, not her own. I saw this happen several times before I figured out that indicating it on your own hand is a sighted way of doing it. Touch is the DeafBlind way. As time goes on, we’ll have more contributors to the blog explaining other features of PTASL and their experiences. We are excited and honored to be a part of this growing movement and looking forward to seeing the impact it will have on the autonomy of DeafBlind individuals everywhere. CHERYL DAVISCheryl Davis is the DBI Project Director. Her role is administrative and evaluative, ensuring the project activities are completed on schedule and within budget, and adhere to the values and mission of the project.  At 8:45 on a Tuesday morning, I walked up the ramp at the Seattle DeafBlind Center ready to meet the colleagues who would help spearhead the national DeafBlind Interpreting project over the next 5 years. Many of us stood in the hallway waiting for the room to be unlocked and had an opportunity to get to know one another. A hand on my shoulder, a tap on my arm, and other indications that we entered a tactile space left me excited and ready to be part of this team. I thought I had some idea of what to expect, but by 9:01 when we walked into the meeting space, I realized I was entering a whole new world and was witnessing history in the making. ProTactile American Sign Language (PTASL) is a promising practice that is changing the way DeafBlind people interface with one another and the community around them. Fueled by the desire for autonomy, DeafBlind leaders are rising up to provide training and resources to other DeafBlind individuals with the goal of changing their community. Now, as part of this federally funded grant project, DeafBlind leaders will train interpreters on the use of PTASL with DeafBlind consumers. Over the course of the next 5 years, a total of 30 DeafBlind mentors, 60 novice interpreters, 45 experienced interpreters, and 10 DeafBlind ProTactile Educators will receive extensive training on the use of PTASL. The goal of this grant is to increase the quality and quantity of interpreters who provide PTASL interpretation to DeafBlind individuals, and to increase autonomy and the use of PTASL in the DeafBlind community. Curious about what comes next? Check back often to learn more about the ways DeafBlind leaders are shaping the face of the DeafBlind community and the field of interpreting one training at a time! Heather HolmesHeather is the DBI Resource Manager. Her responsibilities include development of online materials and courses, management of a national online resource repository, and provision of technical assistance to stakeholders across the country. Join us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/694936277378315/

Western Oregon University’s Regional Resource Center on Deafness is pleased to announce it has received funding to establish a national center on DeafBlind interpreting. Within a framework of evidence-based practice, the DeafBlind Interpreting National Training and Resource Center (DBI) will enhance communication access for persons who are DeafBlind by increasing the number of interpreters able to effectively interpret utilizing tactile communication and other strategies.

Besides training working interpreters in ProTactile ASL and other strategies to meet individual needs, the project will increase the pool of qualified interpreters by building the capacity of DeafBlind individuals to serve as mentors and educators in this specialization, and to build the capacity of VR, interpreter educators, interpreters and other service providers to better serve DeafBlind constituents by giving them the knowledge and skills to incorporate evidence-based practices into their daily work. Project staff include Cheryl Davis (Project Director), CM Hall (Project Manager), Heather Holmes (Resource Manager), and Elayne Kuletz (Web Manager). Primary consultants, Jelica Nuccio and aj granda, will provide in-depth training to interpreters and DeafBlind mentors in ProTactile ASL and mentoring. Approximately 20 content experts from around the country are assisting in the effort. Over the course of the 5 year grant, trainings will be held both on-line and in person. DBI will also serve as a resource center of training materials for interpreters. The project started January 3, 2017, and will continue through December 31, 2021. The project is made possible through a grant from the US Department of Education, Rehabilitation Services Administration, H160D160005; Training of Interpreters for Individuals Who Are Deaf or Hard of Hearing and Individuals Who Are Deaf-Blind program (CFDA 84.160D): Interpreter Training in Specialty Areas. Although no longer officially a collaborative, other Centers funded in the H160C and H160D competitions are:

We look forward to serving you in this new year and beyond! Cheryl, CM, Heather, and Elayne |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed